In which Doris considers the sea and the sun.

On our last morning in El Hierro we drove along the enjoyably-Hebridean road one last time to visit Tamaduste.

Tamaduste is a very good illustration of the perils of writing a guidebook about All The Canary Islands. Once you have opened the chapter on El Hierro by saying that the best thing about it is that it is almost completely undeveloped, you still have the better part of 32 blank pages to fill. “The tiny and charming resort village of Tamaduste” therefore becomes item number 10 on the Top Ten List Of Things To See In El Hierro and with a couple of spare hours before the ferry S&D went there to be charmed, in a tiny way.

Tamaduste is a very good illustration of the perils of writing a guidebook about All The Canary Islands. Once you have opened the chapter on El Hierro by saying that the best thing about it is that it is almost completely undeveloped, you still have the better part of 32 blank pages to fill. “The tiny and charming resort village of Tamaduste” therefore becomes item number 10 on the Top Ten List Of Things To See In El Hierro and with a couple of spare hours before the ferry S&D went there to be charmed, in a tiny way.

Doris admired some creative graffiti which has turned a picture of a dog into one of a goat, Sid played the game of “This is MY house”, and we both took strikingly original pictures of a local rock arch which has probably already featured on a thousand Instagram posts.

The bay itself is indeed cuteness personified, with some strategic amenagement so you can actually get into the water without cutting your pink little toesies to bits on the sharp lava, and so it was time to roll up the trousis and paddle in the actual Atlantic, for the first and only time on this trip.

We wiggled our toes vigorously to create ripples, which, given the interconnectedness of the Atlantic ocean, might one day turn up in Florida where some of our reader(s) may be at the moment. And, as we considered our latitude relative to Florida (at around 27.8°N we are about level with the middle of Florida)(depending on how you define middle, a topic for at least one other post) we also mused on longitude, a topic also beloved of our newest friend Alexander von Humboldt.

Today we didn’t go to visit the memorial to the Meridiano Zero, on the westernmost end of El Hierro down an unsurfaced road which is not recommended for an MX-5, but we did do a bit of research on it. In 1884 the International Meridian Conference was asked to select a prime meridian and selected Greenwich. Most of the attendees approved this, but France was among the three countries that didn’t, and their counter-proposal was a meridian which should “cut no great continent—neither Europe nor America” and which is marked by the memorial. The French turned out to be bad losers, and held out till 1911 before moving to Greenwich time which they still called “Paris mean time, retarded by 9 minutes and 21 seconds” until (this is another good one for a pub quiz) 1978.

Anyway, that alternative meridian is now at a longitude officially called -18.15°. Some more tappy tap research turns up the following information:

– Being 18.15° west of Greenwich means that noon here should be 1h 12 minutes later than at Greenwich.

– The Canary Islands are now on GMT, so we didn’t alter our watches coming here.

– At Greenwich today the sun rose at 8:03 and set of 16:13, giving an effective solar noon of 12:08 on a day length of 8h 10m.

– Today the sun rose here at 8:05 and set at 18:35, giving an effective solar noon of 13:20 on a total day length of 10h 30m. This is, indeed, 1h 12 minutes later than at Greenwich. The whole of the difference in day length of 2h 20m has effectively been tacked on to the end of the day, giving a very pleasantly late sunset.

So far so good but, I hear at least one of our reader(s) cry, why are both the Greenwich and the local solar noons each still a further 8 minutes later than clock time?

For that you need the Equation of Time, and to explain my interest in that I need to digress for a few minutes.

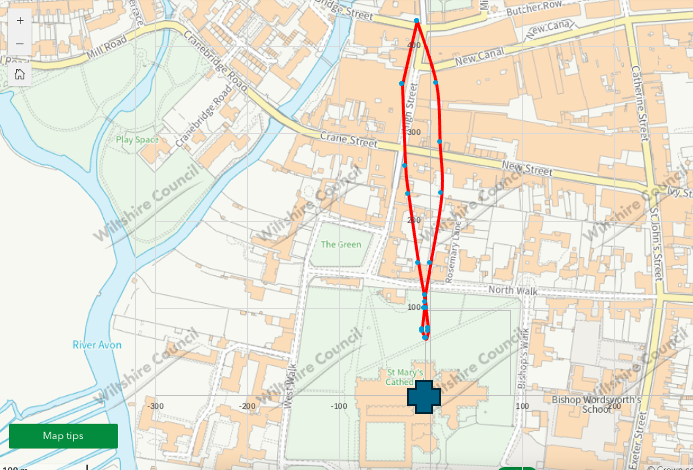

Here in Salisbury there is (apparently) a meridian mark on the cathedral churchyard wall. It’s buried under a thick layer of ivy but it is supposed to mark the point where the centre shadow of the spire points at noon. This got me thinking about the extent that you could use the 404′ (123m) spire as a sort of super-sundial.

With a bit of help from some astronomical tables, and the local council’s detailed planning map of the centre of Salisbury, here is the where the centre of the shadow of the top of the spire lands when the clock shows midday, throughout the year:

This figure-of-eight shaped path is officially called the analemma, and it is a track that anyone can create using only a stick. It is a path that the builders of Stonehenge would certainly have observed, as they had some pretty useful tall stones to use in place of the spire.

And what is so unutterably fascinating is that this line is created from two components:

– the tilt between the Earth’s axis of rotation and its plane of rotation around the sun (this is what causes the days to be longer in the summer and shorter in the winter, and the spire shadow to get shorter and longer), AND

– the fact that the Earth’s orbit around the Sun is not circular but actually elliptical, and this is what causes the shift from side to side in the diagram.

YOU CAN FIND THIS OUT JUST FROM WATCHING A STICK!!!!

I’m sorry, I seem to have got a bit off topic. All that late-night stargazing seems to have got to me.

PS Do take care if you start to investigate any articles about the eccentricity of the Earth’s orbit, or what could be at the non-sun centre of the ellipse, or the meaning of the word barycentre, or the implications of the n-body problem. You could look up and find several hours have passed. As, indeed, have I.

Hey Doris – I don’t have a couple of hours spare to check out the Earth’s orbit (beyond “Currently, Earth’s eccentricity is very slowly decreasing and is approaching its least elliptic (most circular), in a cycle that spans about 100,000 years”) ….so can I just ask you whether that analemma is the same every year (give or take <1 day variation depending on leap year)? Cheers 😊

I think it is the same every year, plus or minus a bit for the leap year effect.

But it would change if you/we travelled south, with the figure-of-eight shape gradually changing to more like an 8.