In which Sid and Doris are surprisingly in the company of Poles and Canadians.

The way out of Ghent takes us along the canals where Sid spots an excellent aid to navigation. Generally a fairly simple map will suffice for inland waterways yet here is a globe, but then this vessel has seen life and maybe too much.

The way out of Ghent takes us along the canals where Sid spots an excellent aid to navigation. Generally a fairly simple map will suffice for inland waterways yet here is a globe, but then this vessel has seen life and maybe too much.

It took a long time for notions of perspective to become embedded in painting. In this picture we can see a vanishing point. Because we know our reader(s) crave variety, this report will not show too many of these. Imagine this for hours at a time. Are we sure about an inland waterway journey?

It took a long time for notions of perspective to become embedded in painting. In this picture we can see a vanishing point. Because we know our reader(s) crave variety, this report will not show too many of these. Imagine this for hours at a time. Are we sure about an inland waterway journey?

We have seen boggling tidiness, such that even Sid thinks it may be a bit obsessive. Doris picks this picture to demonstrate commercial tidiness at the Easter fair. The country we are riding through feels very prosperous. With GDP per head of $48,200 each Belgian has $500 per month more to spend (or spent on them) than each Brit. Their Gini co-efficient puts them in line with Finland and Norway. John Rawls might approve.

We have seen boggling tidiness, such that even Sid thinks it may be a bit obsessive. Doris picks this picture to demonstrate commercial tidiness at the Easter fair. The country we are riding through feels very prosperous. With GDP per head of $48,200 each Belgian has $500 per month more to spend (or spent on them) than each Brit. Their Gini co-efficient puts them in line with Finland and Norway. John Rawls might approve.

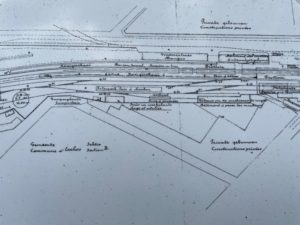

Part of the journey is along the line from Ghent to Bruges via Eeklo, which once had bustling goods yards and marshalling. Here is a morsel of the track plan as drawn in 1927. It is now down to one line in to the terminus of the Ghent to Eeklo line.

Part of the journey is along the line from Ghent to Bruges via Eeklo, which once had bustling goods yards and marshalling. Here is a morsel of the track plan as drawn in 1927. It is now down to one line in to the terminus of the Ghent to Eeklo line.

The gentils organisateurs have guided us to Adagem and a surprising homage to the Polish and Canadian forces who liberated this area (Americans and Brits being busy elsewhere) as the Allies went to Antwerp to re-instate the port facilities. In late summer 1944 all supplies were still coming up from the channel ports, largely by truck (the railways having been bombed) and logistics slowed the advance.

The story is that on his death bed Mynheer Landschoot told his son that during the war he had been hiding men who were otherwise to be sent to forced labour in Germany. He felt that it was only the arrival of the Poles and Canadians that had seen off the occupiers which had saved him and the refuseniks from discovery by the Gestapo or their local agents. So he asked for a museum.

In an anonymous shed on the farm is an amazing collection of vignettes and model panoramas describing the local fighting and some wider context, such as the effects of occupation. See www.canadapolandmuseum.com – the organisers apologise that it is all in Dutch but hopefully that link will take you to the Google Translate utility so you can read it in English. (You may need to flick between Original and Translation to get some of the buttons to work, btw.)

Anyway, back to the real life version of the museum. There are displays of local HQs with all their radio comms. Nearby the Maldagem aerodrome was home to an Me109 squadron and their comms room is recreated. Recognising the role of the bombing campaign there are mock ups of the interior of a Lancaster with navigator’s post, which we regard with particular interest after our visit to Peter Day’s last home in Brussels. Also a room showing the whole of a Lancaster crew receiving a briefing about a mission – the navigator is the one standing up with his back to the camera, and the b/w information pack attached to his jacket is the story of the real owner of that jacket. You are not supposed to take photographs, but we felt we had to just to show you how fabulous the full-size re-creations are.

In the full size set pieces the models are fabulously dressed and equipped, with carefully-selected mannequins having young fresh Canadian and Polish faces. Where they show the Canadian engineers going forward in ali boats the soldiers even have the portage straps to drag the boats through the shallows. There are hundreds of rifles, Sten guns, Schmeissers, Thomsons, MG34s, Brens, Brownings, Mauser broom handles, Lugers, Swedish made snipers’ rifles, Lee Enfields and mortars in all the popular (or unpopular, depending on which side you were on) sizes.

Using 1/35th models the local campaigns are recreated in slightly overcrowded but obsessively-detailed miniature. There may be part of the Tamiya catalogue missing but Sid can’t think what it would be.

It is an astonishing thing and it goes on for room after room. We are told that many of the uniforms we are seeing ended up in attics in the local area because as the men fought their way across this waterlogged land they were soaked and muddy. Locals gave them clean and warmer farming clothes, saying they would wash and dry the wet kit, it would be ready when the guys came back. But they went forward leaving their kit to be reverently preserved. The museum owners’ aim is to trace the personal story of every uniform in the museum, hence the b&w information pack you saw on the navigator’s uniform above.

Many of the Polish uniforms have come directly from their original owners because when it was time to go back home the Russian puppet regime wouldn’t have them. They remembered being feted in Flanders and returned to live. Their families are here now, and when the Polish part of the museum was set up in 2004 they donated their uniforms and other artefacts.

Sid and Doris emerge outside in a sort of satiated but sober daze, as the similarities between WW2 fighting here 77 years ago and Russia/Ukrainian activity being reported now are rather unsettling.

Sid and Doris emerge outside in a sort of satiated but sober daze, as the similarities between WW2 fighting here 77 years ago and Russia/Ukrainian activity being reported now are rather unsettling.

Our organisers had observed that there is a steam train museum in Maldegem too, but today (and in fact most days except Wednesdays and Sundays) it is Verboden Te Gaan there. No big deal as our heads are still full of young men and women in WW2.

In Maldagem we are in a somewhat plain hotel out in the fields but hearty fare is only a hearty bike ride away.