In which Sid and Doris find that the Highlands are not high.

We enjoy the morning walking out over elegant Victorian pedestrian suspension bridges, along the Ness Islands. These little white-painted suspension bridges have been a feature of our river-side driving ever since Balmoral – we suspect that the wily Scots bought a single pattern from the original designer and then turned them out to order in whatever width your river was.

We enjoy the morning walking out over elegant Victorian pedestrian suspension bridges, along the Ness Islands. These little white-painted suspension bridges have been a feature of our river-side driving ever since Balmoral – we suspect that the wily Scots bought a single pattern from the original designer and then turned them out to order in whatever width your river was.

We cross to the Caledonian Canal and follow it back towards town, the swing bridge and flight of locks that takes boats from sea level to a height that will put them down the Great Glen and Loch Ness. This is another masterpiece by Thomas Telford; did he never tire? You can take a masted vessel from coast to coast. This morning we saw “Supertramp” a serious 45′ ocean going yacht underway going West. Reading their flags and hailing them, we think they may have come from Australia.

In town we find the Flat Earth Society Shop with a range of conspiracy theories in the window.

[Sorry the picture is a bit indistinct – I took it from a distance and scuttled away as I became convinced that one of their staff was looking at me oddly – D.]

The virus is a hoax perpetrated to cow the populous, which is good to know. The hoax has clearly taken hold as the Scottish government has just shut all hospitality across the central belt.

Though we are all the way up on the North coast new and bizarre rules will apply from next week. The Forss Hotel, our home tonight, did their best to book us in to eat at 6pm. We held out against nursery tea and are eating with the grown ups.

The cathedral and pretend castle got a cursory look and we set off over the Moray Firth heading for The Highlands. Taking the cross country route Doris soon has us up to Lairg, to eat and swap seats. [To eat, and then, to swap seats. D.] The Autumn colours come up better in the eye than in the camera.

The cathedral and pretend castle got a cursory look and we set off over the Moray Firth heading for The Highlands. Taking the cross country route Doris soon has us up to Lairg, to eat and swap seats. [To eat, and then, to swap seats. D.] The Autumn colours come up better in the eye than in the camera.

After Lairg the Highlands are rolling hummocks hills with meandering streams crossed by single track roads – these are the main roads so we are sharing them with determined professional drivers. The Mini is small but it is not that small, and the verges look very squishy so we dive into the passing spaces.

Rain comes, and rain goes. Sid counts the rain. Doris counts the rainbows.

We drive on through countryside that strongly resembles the pelt of an Aberdeen Angus cow. Brown, lumpy and damp. It is not entirely clear why these are called the Highlands.

As earnest seekers after local history we are on our way to Rosa(i)l and so we whizz on past the Crask Inn. With the debatably attractive claim of being “Scotland’s most remote inn”, its commercial potential is illustrated by the fact that its previous owners gave up trying to sell it and donated it to the church.

We take more single track A and B roads to find Syre village and the site of Rosal village, which in 1814 was cleared of its population by Patrick Sellar, factor for the Countess of Sutherland. She wanted improvements by which she meant sheep on the land and the people gone. About 70 people lived at Rosal, essentially subsistence farming corn, cattle, sheep and goats. They were powerless in the face of the factor’s men who put them out of their homes and chased them away. To stop them coming back the houses were knocked down and the heaps of stones are here for us to see.

Of course this is still happening where The Party or just men with guns come. But perhaps we might have hoped for better in the United Kingdom by the early 19th century. In Edinburgh the enlightenment thinkers had rejected authority, religious and secular, that could not be rationally defended. Still, men with guns paid by the mighty did their work. In this case the factor became the tenant and ran a profitable sheep business.

Sutherland was a long way from Edinburgh or anywhere. Even so Scottish Forestry had closed the ‘car park’ (place down a rough track). Up here two metre distancing will be a challenge. One person per hectare would be a busy day.

Sutherland was a long way from Edinburgh or anywhere. Even so Scottish Forestry had closed the ‘car park’ (place down a rough track). Up here two metre distancing will be a challenge. One person per hectare would be a busy day.

We walk for half a mile through a damp wood to admire some damp mounds of bricks. There is a solar-powered commentary machine, and we are content, in a Sid-and-Doris sort of way. Top-quality 4G phone signal reminds us that remote places can be better-connected than the villages round Bishop’s Stortford.

Pausing to mourn briefly the death of a small hairy toothy thing (because someone should), we drive away on the B871 and pass “Garvault”, which claims to be the UK’s most remote mainland hotel. There is so much nothing that the music for today must be We’re on the Road to Nowhere.

Pausing to mourn briefly the death of a small hairy toothy thing (because someone should), we drive away on the B871 and pass “Garvault”, which claims to be the UK’s most remote mainland hotel. There is so much nothing that the music for today must be We’re on the Road to Nowhere.

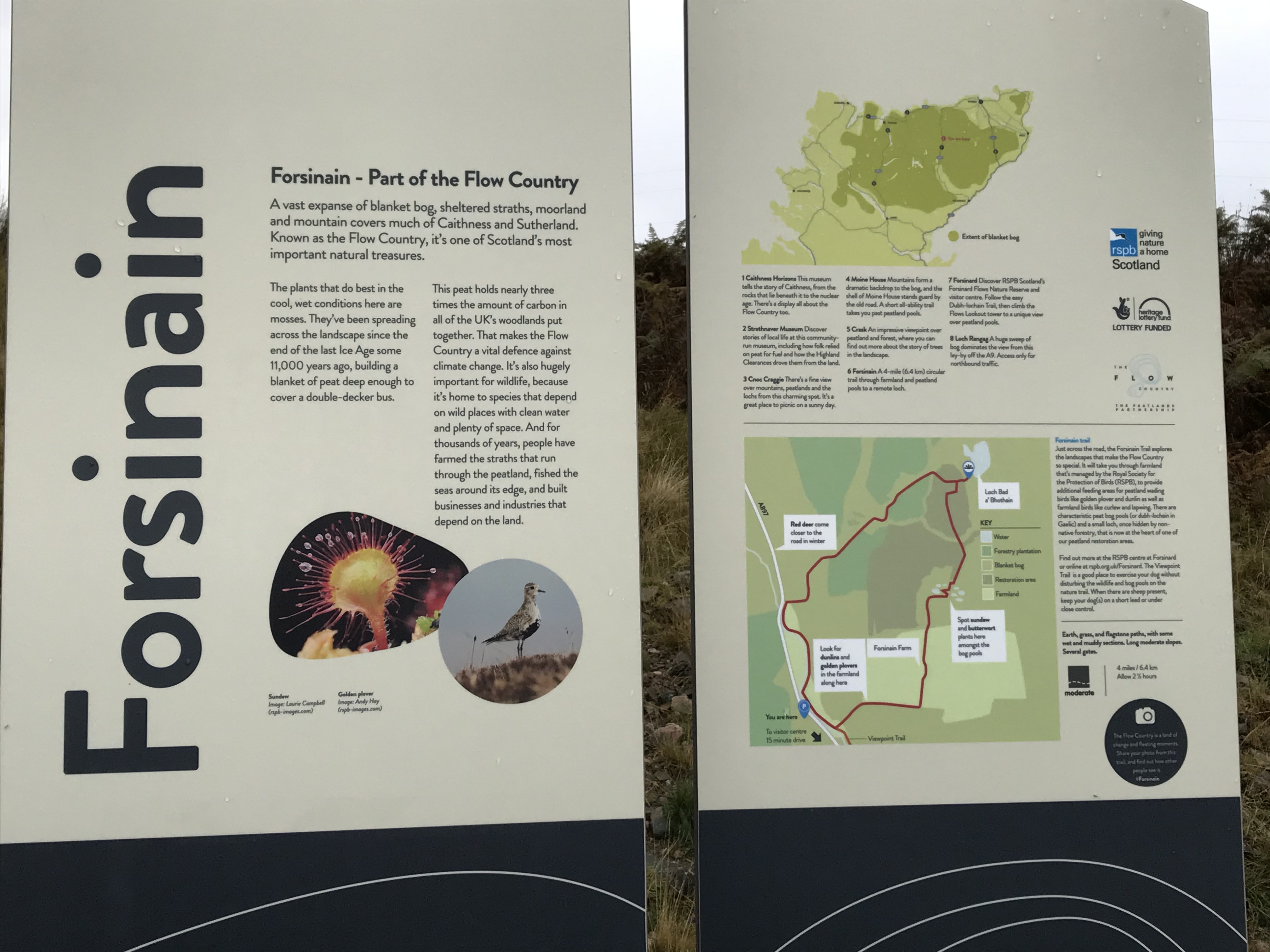

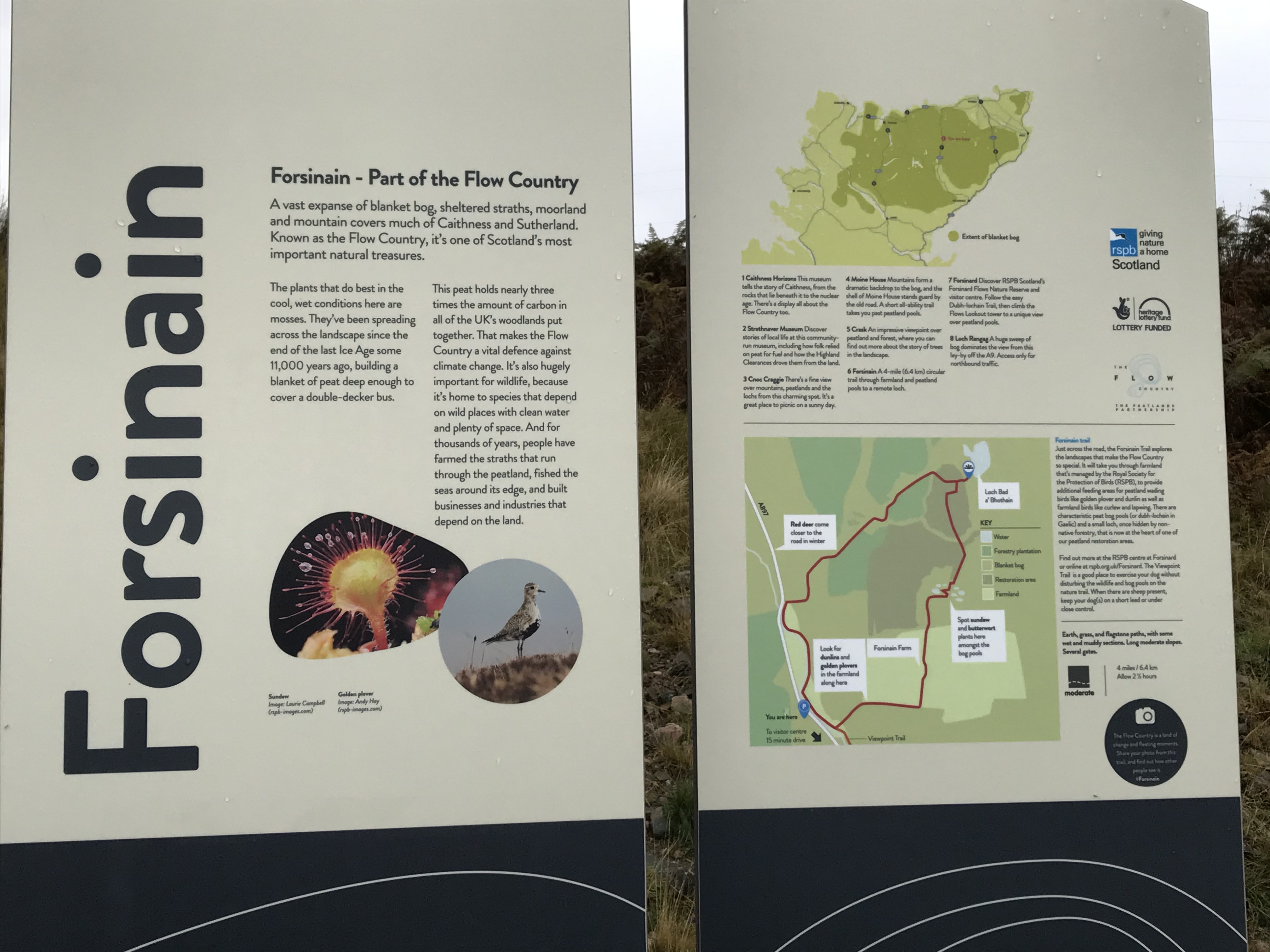

We were surprised to find at Forsinain we had been somewhere with significant nature. It is called Flow Country and the peat holds three times the amount of carbon than in all of UK woodland put together. Think of it as immature lignite?

We were surprised to find at Forsinain we had been somewhere with significant nature. It is called Flow Country and the peat holds three times the amount of carbon than in all of UK woodland put together. Think of it as immature lignite?

To get away from burning stuff humankind got around to nuclear power. Soon we are passing a suspiciously rusty-looking Dounreay power station. Commissioned in 1955 it was a fast breeder reactor and ran until 1994. Nuclear did look like the future.

Dounreay should be a brownfield site ready for some other use by 2336 if all the decommissioning goes to plan. Maybe we can do something with wind and solar?

We pause briefly and look North. We are on the flat top of the UK, and there is nothing between us and whatever remains of the Arctic ice. Everything we know is behind us, and we are on the final page of the road atlas.

We pause briefly and look North. We are on the flat top of the UK, and there is nothing between us and whatever remains of the Arctic ice. Everything we know is behind us, and we are on the final page of the road atlas.

We enjoy the morning walking out over elegant Victorian pedestrian suspension bridges, along the Ness Islands. These little white-painted suspension bridges have been a feature of our river-side driving ever since Balmoral – we suspect that the wily Scots bought a single pattern from the original designer and then turned them out to order in whatever width your river was.

We enjoy the morning walking out over elegant Victorian pedestrian suspension bridges, along the Ness Islands. These little white-painted suspension bridges have been a feature of our river-side driving ever since Balmoral – we suspect that the wily Scots bought a single pattern from the original designer and then turned them out to order in whatever width your river was. We cross to the Caledonian Canal and follow it back towards town, the swing bridge and flight of locks that takes boats from sea level to a height that will put them down the Great Glen and Loch Ness. This is another masterpiece by Thomas Telford; did he never tire? You can take a masted vessel from coast to coast. This morning we saw “Supertramp” a serious 45′ ocean going yacht underway going West. Reading their flags and hailing them, we think they may have come from Australia.

We cross to the Caledonian Canal and follow it back towards town, the swing bridge and flight of locks that takes boats from sea level to a height that will put them down the Great Glen and Loch Ness. This is another masterpiece by Thomas Telford; did he never tire? You can take a masted vessel from coast to coast. This morning we saw “Supertramp” a serious 45′ ocean going yacht underway going West. Reading their flags and hailing them, we think they may have come from Australia. The cathedral and pretend castle got a cursory look and we set off over the Moray Firth heading for The Highlands. Taking the cross country route Doris soon has us up to Lairg, to eat and swap seats. [To eat, and then, to swap seats. D.] The Autumn colours come up better in the eye than in the camera.

The cathedral and pretend castle got a cursory look and we set off over the Moray Firth heading for The Highlands. Taking the cross country route Doris soon has us up to Lairg, to eat and swap seats. [To eat, and then, to swap seats. D.] The Autumn colours come up better in the eye than in the camera. After Lairg the Highlands are rolling hummocks hills with meandering streams crossed by single track roads – these are the main roads so we are sharing them with determined professional drivers. The Mini is small but it is not that small, and the verges look very squishy so we dive into the passing spaces.

After Lairg the Highlands are rolling hummocks hills with meandering streams crossed by single track roads – these are the main roads so we are sharing them with determined professional drivers. The Mini is small but it is not that small, and the verges look very squishy so we dive into the passing spaces. Sutherland was a long way from Edinburgh or anywhere. Even so Scottish Forestry had closed the ‘car park’ (place down a rough track). Up here two metre distancing will be a challenge. One person per hectare would be a busy day.

Sutherland was a long way from Edinburgh or anywhere. Even so Scottish Forestry had closed the ‘car park’ (place down a rough track). Up here two metre distancing will be a challenge. One person per hectare would be a busy day. Pausing to mourn briefly the death of a small hairy toothy thing (because someone should), we drive away on the B871 and pass “Garvault”, which claims to be the UK’s most remote mainland hotel. There is so much nothing that the music for today must be We’re on the Road to Nowhere.

Pausing to mourn briefly the death of a small hairy toothy thing (because someone should), we drive away on the B871 and pass “Garvault”, which claims to be the UK’s most remote mainland hotel. There is so much nothing that the music for today must be We’re on the Road to Nowhere. We were surprised to find at Forsinain we had been somewhere with significant nature. It is called Flow Country and the peat holds three times the amount of carbon than in all of UK woodland put together. Think of it as immature lignite?

We were surprised to find at Forsinain we had been somewhere with significant nature. It is called Flow Country and the peat holds three times the amount of carbon than in all of UK woodland put together. Think of it as immature lignite?